Uncertainty is a recurring theme these days. Most people are worried about the pandemic, about the economy, about politics, about relationships, about their jobs, and so on. A lot of these these things are uncertain; nobody knows what’s going to happen with the current pandemic, where the economy will be in a few years from now, or even what is going to happen in our relationships. Constant worrying creates anxiety. As human beings, we have a natural tendency for “control”, wanting to be in control of things – and uncertainty is not compatible with control. While definitely uncomfortable, anxiety is also kind of a natural reaction to uncertainty.

As a psychologist, I am confronted with uncertainty and resulting anxiety on many sides: it affects my clients and how I work with them, but it also affects my personal life. Today’s article is intended to provide some information about uncertainty, anxiety and how to deal with uncertainty in these unprecedented times. Disclaimer: Please note that my blogs do not replace professional advice from health providers.

Anxiety, stress and fears as natural and normal reactions: Autonomic nervous system

One of the first things I do with new clients, and I also bring it up constantly later on, is to explain how our body works. It’s important to get an idea about how emotions works, how stress works, and what your body is doing. Working with my clients, it is very important for me to explain how stress and anxiety work on a physiological level.

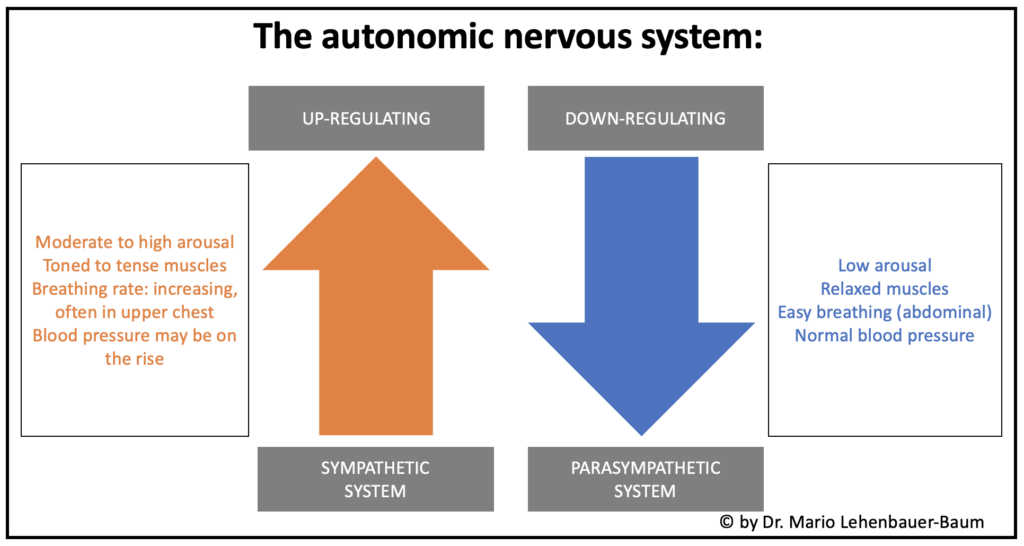

Talking about stress and anxiety, I usually explain how our autonomic nervous system works. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulates most of our body processes without our conscious effort (which is why it is called “autonomic”), and it includes processes like heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, digestion, sexual functions, etc. (imagine if we would have to consciously *think* about breathing all the time!).

The ANS has two main divisions (actually, there are three, but I usually leave out the third branch – the enteric system – because the enteric system is capable of functioning independently from the nervous system, and is mainly responsible for digestive processes); those two divisions mostly compete with each other (which means, they usually cannot be activated at the same time):

- The sympathetic nervous system “activates” our body and is responsible to prepare us for stressful or emergency situations. It is connected to our “fight-flight” response, and increases our heart rate, we breathe faster, we feel more alert, etc. It activates us, and it prepares our body to do something, to “fight” something, or to run away really fast (flight).

- The parasympathetic nervous system mainly inhibits body reactions, it “slows” us down. We feel relaxed, calm, the body is ready for “rest and digest”; the heart rate is slowing down, the breathing pattern changes (slower and more deeper breathing into our belly), etc.

Think about how you feel, what you feel in your body, when you think about stress and anxiety – you probably already know how it makes you feel: your heart rate increases, your hands may feel shaky, you may feel on edge, etc. These are all reactions governed by the autonomic nervous system. I am using stress and anxiety synonymously here, because they overlap a lot in the way our body reacts to them.

We need both systems to function and perform well in our everyday life. For example, driving a car requires our attention; we need to be activated and to be ready to react quickly to danger (e.g., when a car brakes in front of us). However, we cannot be alert AND at the same time feel “relaxed” or “tired” because the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous system are mostly incompatible with each other (either A or B is activated at the same time).

Anxiety, stress and fears “activate” us; our reactions to anxiety and stress are very similar on a physiological level. Our brain recognizes “danger” and puts our body into an activated, more alert mode. This is extremely important for our survival; for example, if a venomous snake appears in front of us and attacks us all of a sudden, we need to be prepared to run away really fast. However, sometimes the “threat” is less real, more diffuse and not tangible at all.

Being in control: anxiety and uncertainty

In general, human beings love to be in control. We love being able to plan (for) things, to anticipate outcomes. However, we are also hardwired to notice things that may be threatening to us. During unprecedented times, where we all are confronted with a global pandemic, many of us feel like we are in danger and like there’s not much we can do about it. We don’t know outcomes, we feel like we can’t control the spread of the virus, we feel like we can’t control how long we have to stay at home – it seems like there are too many things that are uncertain, that we cannot control.

Whenever life feels uncertain and we cannot control certain situations, we feel stressed and/or anxious. The sympathetic nervous system take over; it tries to “active” and “prepare” us. It wants us to take actions to be in control again; most of us are hardwired to take actions whenever we feel like we are not in control. This natural reaction is there to protect us from danger. If you wouldn’t feel anxious, you probably wouldn’t care about consequences, and you wouldn’t wash your hands multiple times per day, or wouldn’t care about wearing masks, etc.

A certain level of anxiety can therefore be useful for our survival, so we can control certain outcomes. However, if we are too worried about too many things, all of our sudden our brain tries to prepare us for too many things at once, and we get too anxious or overwhelmed.

The current pandemic may make us feel helpless about the future; we hear many conflicting information on the news, and things change(d) very quickly. Our natural tendency to be in control is not compatible with the current level of uncertainty about the pandemic; we simply don’t (always) know what is going to happen. Whenever things or situations are uncertain, our body tries to be “activated” and “prepared” for whatever is going to happen. Once we feel like we are in control again, we feel like we can relax (and “breathe”) again.

While these reactions are normal and necessary, it can also be detrimental for our mental health, especially if we are too “activated” for a longer period of time. Some people feel angrier, some feel more “on edge”, some feel helpless, sad or more depressed than usual; dealing with uncertainty interferes with our innate desire to be in control.

How to take back some level of control: Create a routine

When you think about your life before the pandemic, you probably remember that you had a routine with certain rituals. You got up every morning to shower, you had your coffee at home, you read the news, you went to gym to work out, etc. These “little” things are very important because they give us a feeling of certainty and normalcy. Now, having to stay at home, or having to work from home, it messed up our routines. All of a sudden, we have to stay inside, we cannot go to gym, we cannot go to the mall whenever we want to – our daily routine is messed up, and that level of certainty is seemingly gone.

There are many things that we cannot control with the current pandemic, like, how long it will take, and how it’s going to play out. However, there are still many things that we still have control over, and one of them is our daily life and our daily routine.

There are still the seemingly “little” things that you can do, and it is really important to focus on those. I usually recommend it to any of my clients these days that they create a new routine; it is important to have your own little things that you can do every day. It should be a routine that you can stick to and that makes you feel better. Try to create a plan for the next 2-4 weeks, with all the “little” things you can do every day.

It’s also very important to plan “self-care” as well, now more than ever. Do anything that makes you feel more calm and relaxed (and to give your body the chance to be more calm): it can by anything, a warm bath, play time with a pet, cuddle time with a partner, reading a good book, or – if you are located in South Florida – a walk on the beach.

At the end of the day, try to be kind with yourself; we all live during very unprecedented times, almost none of us had to live through a pandemic like this before. It is okay to not feel okay sometimes, but it is very important to give yourself permission to do something that makes you happy. Make the best out of your days and weeks, and try to create and stick to a routine; it is one of the first steps you can do to gain back some level of control.

Also, it is important to know that anxiety and worries are usually centered around possible outcomes in the future (“What if…”). Challenge yourself to stay in the present, and if you have to think about anxieties and worries, try to view it in terms of possibility and probability. Anxiety is usually centered around possibility; literally anything is possible! However, how LIKELY (probability) is it that something is going to happen? Anxiety and worries want us to feel activated for any possible situation, so it is important to remind yourself that not everything that’s possible is also likely going to happen.

Don’t hesitate to reach out to friends, family, or trained mental health professionals for support. Especially these days and weeks, most mental health providers (including myself) switched to providing Telehealth services (online only), making it easier and so much more convenient for people to access mental health services from the comfort of their own home.

About the author: Mario Lehenbauer-Baum is a licensed psychologist, located in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In his private practice, he focuses primarily on anxieties/phobias, adult ADHD, issues with relationships and sexuality, and general men’s issues. He offers Telehealth services as well. This blog is intended for entertainment and information purposes; however, Dr. Mario Lehenbauer-Baum is not responsible for any actions you may or may not take based on information from this blog. This blog does not replace therapy or counseling, and it does not replace any professional advice from health care providers.